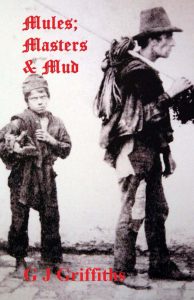

Mules; Masters & Mud by G J Griffiths

Mules; Masters & Mud by G J Griffiths

WARNING! This book may contain NUTS! (Non-Uniform Text Speech)

In other words speech in what some have called “Olde English Vernacular”. It is spoken by characters in the book from the North, the Midlands and the South of England. There is a glossary at the end of the book to help if you can rise to the challenge. It adds shades of colour to this 19th century story that you may not be expecting.

When Mrs Alexander wrote about “the rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate” and declared that “God made them, high or lowly, and order’d their estate” in the ever popular hymn All Things Bright and Beautiful, she was probably reflecting one of the mores of the times. It would fit in well with prejudices and beliefs of the middle and upper classes that paternalism had indeed been intended by God, thus laws protecting the workers in their fields, mills and factories were not necessary. In the words of Browning so long as “God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world!”

The continuing story of the Quarry Bank Runaways is about what happened to two cotton apprentices over three decades during the Industrial Revolution; first as qualified young men with hopes and later when they are full grown. By the start of the Victorian period the fates and their ambitions would have collided. Serious events and incidents, both personal and national, were about to impinge upon the lives of Thomas Priestley and Joseph Sefton, who had earlier run away from their apprentice master, Samuel Greg. What would cause a qualified mule spinner to give up his comparatively safe job and risk failure, ridicule or destitution? Ambitious and determined working class individuals like Tommy and Joe had to carefully step through a pathway involving love, loyalty and legal persecution and prejudice, from within the social hierarchy of the times.

Targeted Age Group:: YA and adults

Heat/Violence Level: Heat Level 3 – PG-13

What Inspired You to Write Your Book?

Thomas Priestley and Joseph Sefton were skinny teenage boys, paupers, taken from their mothers as small children to live in the Apprentice House and work in the cotton mill in Quarry Bank, Cheshire. Injured and desperate they sneaked out from the mill in 1806 to walk 200 miles to London in order to see their mothers in Hackney workhouse. They did see them but it was after a week of adventures and, after an appearance in Middlesex Courthouse, where they were charged with breaking their indentures to cotton king – Samuel Greg.

I worked as a volunteer tour guide at Quarry Bank Mill Museum for many months learning about the history of the mill, and discovering some of the real stories about children as young as 9 who worked there, often for no wages! Accumulating even more of the mill’s background historical tales as I progressed with my volunteer experience inspired me to write the two books. This sequel is called Mules; Masters & Mud and tells about the apprentices’ lives during the next three decades after their appearance in Middlesex Courthouse. It relates the events, trials and tribulations around the two as adults – right up until the death of Samuel Greg, the millowner, in 1834.

How Did You Come up With Your Characters?

The two main characters, Thomas and Joseph, were real boy apprentices who lived during the Industrial Revolution early in the 19th century. I used some of their real life experiences to create the plot for two historical novels as I described above in my synopsis and inspiration.

Book Sample

An extract from Mules; Masters & Mud – the sequel to The Quarry Bank Runaways.

It is the chapter about the runaway apprentice Thomas Priestley when, as an adult, he is wounded while attending what became known as the Peterloo Massacre.

Chapter Ten: Injury

On a fine sunny morning in August 1819 Thomas, with eight other cotton workers, was travelling on a horse drawn cart to Manchester. The road from Mellor was not one of the best in wet weather, but the rain had stopped as they joined the turnpike road, passing through Stockport, to pick up Tommy and some other club members, when everyone was in high spirits. They were all looking forward to hearing Henry Hunt speak to an assembly of people on Parliamentary reform and against the Corn Laws, for which the high price of food was being blamed. The many peaceable workers, like Thomas, had high hopes for a non-violent orator like Hunt to bring to the attention of the government the claims of “ordinary folk” of the causes for the many hardships in their lives. It was rumoured that hundreds would be there in St. Peter’s Fields and that it would remain peaceful enough for women and children to be present.

‘Wotcher, Tommy, ’ow’s things?’

‘Pretty fair, Jacob, pretty fair… What’s that clothes prop for, then? It looks like a flag.’

‘Clothes prop? Nay, mate that’s me banner demandin’ the vote, ain’t it.’

Jacob was a secret convener of club meetings and groups for the surrounding mills of Stockport. He had become quite a confidante of Thomas and Will Souter and kept them informed as much as he could about changes in employment law and other developments. He had listened to Francis Place speak against the Combinations Acts and had joined the march two years earlier when the workers had hoped to present a petition to the Prince Regent in London. The large group of protesters had walked but a few miles south of Manchester when troops had broken it up, causing more dissidence to spread to many more workers.

There were eight leather flagons on the cart with contents that added much to the holiday mood amongst the men aboard. As soon as the scrumpy cider had all disappeared everyone was agreed the ale would be most welcome. Even with an early morning start to the journey the cart was not going to reach Manchester much before lunchtime. Frequent stops for the relief of eight bladders had a lot to do with the delays and word had reached the pie-men and other purveyors of food about the meeting on St. Peter’s Fields. The suppliers of such refreshments were scattered along the route every half mile or so and they were doing well. The cart from Mellor found it was one of very many by the time they reached Ancoats. Most of the men on the cart had never been to Manchester and while they were most impressed by the many enormous mills that towered above them, they were alarmed to see how densely populated the area was. Dozens of people walked to and fro while small gangs of small children played in the filth.

‘Where do all these people live?’ asked Thomas.

‘Why in these tenements an’ back-to-back houses, Tommy. Oh, an’ though they’ve got better roads around ’ere it’s for the convenience o’ the mill owners an’ merchants, see: for the transport o’ bales an’ what ’ave thee.’

‘Look at the state o’ the roads,’ said Tommy.

There were piles of discarded bits of broken furniture, rotting vegetables, filthy soiled clothing and stinking excrement littering the sides of a yellow stream. The yellow stream was an open running sewer that would eventually find its way into the Rochdale Canal or either of the rivers Mersey or Irwell.

‘Aye, an’ ’alf these ’omes ’ave got no privies or plumbin’, pal,’ said Will. ‘No surprise, there’s so many poor kiddies dead afore they’re ten around the town, eh,’ he continued. ‘Thee can nigh see th’ miasma that’s acomin’ up off them streets; causin’ all sorts o’ diseases, see.’

The wagoner driving the cart was attempting to find a way through Redhill Street and as they passed by the enormous eight storey edifice that was McConnel’s Mills he told Jacob that he was about to stop.

‘See, Jacob, ah needs ter find a farriers ter attend to me hoss… Mebee, a stable somewhere round ’ere, if ah can… Hoss is trottin’ a bit lame, see.’

‘No problem, mate,’ replied Jacob. ‘It ain’t that far ter walk from here… Ah knows the right road. We go past th’ Infirmary on Piccadilly?’

The wagoner nodded and the workers got down from the cart, still in high spirits, chatting about the high hopes they had about Orator Hunt and what they expected to hear in his speech. There were no open public spaces neighbouring the many mills; no parks for the group to stroll through or sit and chat; no public buildings nor churches with churchyards. Everything about the place where they had stopped was about cotton: scotching it; carding it; spinning it; weaving it and selling it. They were in the growing heart of Cottonopolis.

The group from Mellor and Stockport were amazed to see dozens of wagons and carts lined up around the streets bordering St. Peter’s Fields. But the sheer numbers of happy people, men, women and children, congregating upon the site meant for the speeches was a shock – there were many, many thousands and they all seemed to be in the same holiday mood as all of the club members. There were sideshows, entertainers of all kinds, pedlars and stalls with refreshments; the carnival atmosphere belying the serious nature of the reasons for such an assembly of thousands from the working classes of the north of England. Henry Hunt’s reputation as a radical reformer had reached the local magistrates and they had called upon the Yeomanry of Manchester and Cheshire to stand by in case of insurrection from the crowds. A narrow passage, lined by constables, allowed Hunt and others to approach the raised platform amidst the packed assembly and the suffocating heat of the middle of the August day. Watching from his room at the corner of St. Peter’s Field the chairman of the magistrates was encouraged by Hunt’s enthusiastic reception to issue warrants for the arrest of the speakers and send orders for dispersal of the assembly. He feared for the preservation of the peace, ensuing riots and, therefore, that lives and property were in danger; not only that but he assumed what he saw was but a part of a nationwide rebellious movement.

The speeches began; banners were waved; repeal of the Corn Laws was demanded; shouts and cheers followed; universal suffrage was reasonably demanded; more cheers and cries of: ‘Hear, hear! Well said, sir! Hurrah, that’s right!’ could be heard above the holiday hum of the crowd. Up on their platform Hunt and his entourage were growing ever more animated and arms were raised, waved in the way of many a country church choir master. The people, many still dressed in their plain working clothes, were unaffected by the contrast with the fine apparel worn by the lecturers. Ordinary people were whooping and applauding with such exuberance that they could be heard miles away. The swelling sound was now about to be misinterpreted by the Yeomanry, strategically assembled to the west and east of St. Peter’s Fields, supported by hundreds of constables and a company of hussars. The poorly trained, volunteer cavalrymen of the Yeomanry were commanded by Captain Birley, who was also a local factory owner.

It was not ten minutes after one thirty when the captain led his cavalry towards the platform of speakers. This was to assist the chief of constables and his men in the arrest of those same speakers. In attempting to force their way through, the horsemen lost all sense of self-control and drew their sabres, hacking their way through everyone in their path, men, women and children! In the panic of people trying to get out of the way the untrained horses reared and plunged into them, injuring many more. When the arrest warrant had been served by the police officer, the Yeomanry then set about seizing and destroying the many flags and banners, and to disperse the crowd further. But this was not possible while the main exit from the area was blocked by rows of foot soldiers with fixed bayonets.

Thomas and Jacob became incensed at the sight of a large group of flag-carrying women from a female reform society, all dressed in white, who were being savagely attacked by horsemen. More spilt blood conflicted horribly with the white dresses of the women and a few brave souls attempted to defend themselves with their short flag staffs. With eyes as wild as those of their steeds the cavalrymen slashed out, not caring whether the flags parried their deadly sabres or whose head was split open.

‘Come on, Jacob!’ yelled Thomas as he flung himself forward at one of the horsemen and held on to his weapon arm. The man would not be pulled down from the saddle and received a hefty blow to his back from Jacob’s banner pole. This was then a signal to the soldier’s comrades to turn their attention to the two men and rain blows upon them. Thomas and Jacob were not alone in attempting to return the fight physically, while the many brickbats and loud curses from the people heard by the magistrates caused them to rouse the hussars into the fray.

‘The crowd must be dispersed! The yeomanry are now being assaulted! Go to it!’ they ordered the officer commanding the hussars. Within ten, or maybe, fifteen minutes the assembly in St. Peter’s Fields had been dispersed, although riots continued throughout the streets of Manchester for hours. Bloodied and injured bodies in their hundreds strewed the area and later it was found that there were eleven fatalities among them, including nine men and two women. Thomas and Jacob, with three of the women reformers, lay unconscious where they fell. They were surrounded by others, similarly wounded and bleeding, unable to hear the groans and cries of pain that arose like an invisible cloud of doom over the field.

The majority of the ruling classes did not save their blame and recriminations just for those working class people who were able to walk away from St. Peter’s Fields free of injury. Many of the wounded did not seek medical treatment for they were certain that it would invite retribution from the authorities. Rumours of such a spiteful attitude had a strong basis in fact. The mill owner who had captained the unruly yeomanry, one Hugh Birley, was greatly offended when he discovered that one of his male workers had dared to attend the meeting in St. Peter’s. His hurt and annoyed feelings were somewhat appeased, however, when he subsequently sacked the three sons of the man later. The surgeon in the Infirmary who was attending to the wounds of some of the workers brought there had definite views about the ‘upstarts’ from the lower classes learning a suitable lesson as a penalty for their ‘crimes’. Unfortunately, Thomas and Jacob were two of those on the receiving end of the surgeon’s disciplinary measures as they lay awaiting treatment.

‘The sabre wounds to your heads are going to need sponge cleaning and packing, gentlemen. The redness and pus that is forming indicates to me that wound fever has begun, but of course that is quite normal where sepsis is concerned. Are you in pain?’

Both men had not ceased groaning since they had recovered consciousness and the red swelling around the cuts was considered by the surgeon to be a sign of healing, rather than one of serious infection. Their bodies and limbs were covered in bruises and this was considered to be of very little concern. Jacob’s cuts to his crown and ear were deeper than those to Tommy’s head and arm and causing him considerable pain.

‘Will thou see ter me companion first of all, sir? I think he’s a sufferin’ most,’ said Thomas.

The surgeon drew closer with his bowl of vinegar water and the same cloth that he had been using all afternoon.

‘I expect you two foolish fellows will be returning to work peacefully quite soon. No doubt you’ll agree that you’ve had your fill of these ill-advised Manchester meetings.’

Despite the pain and the temptation to swoon again into a state of unconsciousness Thomas and Jacob shook their heads, just a little, as much as the soreness would allow.

‘Oh, no, sir; our cause is just. We mun stick together an’ demand the vote an’ better workin’ conditions,’ answered Jacob.

‘While them laws as keeps the price o’ bread up too ’igh is there we gotter keep goin’, sir. Folks is starving’ while wages is pressed down by factory owners,’ added Thomas.

Their replies appeared to upset the disposition of the surgeon. The discussion that followed, for more minutes than the time it took the hussars and cavalry to disperse the assembly of people, was a diatribe from the medical man versus an insistence of more rights from the two wounded men. It ended when the surgeon ordered the pair to be taken away by their friends and to be taken ‘back to whence they came’ – untreated!

Links to Purchase Print Book version – Click links for book samples, reviews and to purchase

Buy Mules; Masters & Mud Print Edition at Amazon

Buy Mules; Masters & Mud at Barnes and Noble

Links to Purchase eBook version – Click links for book samples, reviews and to purchase

Buy this eBook On Amazon

Buy this eBook on Barnes and Noble for Nook

Buy this eBook on Kobo

About the Author

Learn more about the author on their website

Follow the author on Amazon

Follow the author on Social Media:

All information was provided by the author and not edited by us. This is so you get to know the author better.